Hello,

Below is the info about another interesting panel taking place at IFPRI. The issue to be discussed will be investment in Agricultural Research and Development. With privatization, budgetary constrains, and decentralization, R&D has decreased enormously in the past decade. Although we have seem magnificent benefits such as the Green Revolution, Sub Saharan Africa, Central America, and other parts of the world are lagging behind in terms of yields, infrastructure, inputs markets, and commercialization. In these areas, public R&D must play an essential role in ensuring small and medium scale farmers are getting adequate information to become competitive. We already know that the returns on investments in Ag R&D are huge; now he need more political commitment from the local governments and the international donors. If you cannot make it to the event, check this article by Marc Cohen on R&D for Agriculture "Aid to Agriculture and Rural Development"

**** Panel Discussion****

Agricultural Research -- A Growing Global Divide

Nienke Beintema, IFPRI

Philip G. Pardey - University of Minnesota

Dana G. Dalrymple -- USAID

Isi A. Siddiqui -- CropLife America

Monday, 13 November, 2006

3:30 - 5:00 p.m.

Abstract

Sustained, well-targeted, and effectively used investments in Research

and Development have reaped handsome rewards from improved agricultural

productivity and cheaper, higher quality foods and fibers. At the

beginning of a new millennium, the global patterns of investments in

agricultural R&D are changing in ways that may have profound

consequences for the structure of agriculture worldwide and the ability

of people in poor countries to feed themselves.

What are the key trends in agricultural R&D spending?

What are the implications of the changing trends in agricultural R&D

spending?

What are the developments in public and private sector investment in

agricultural R&D?

Please join us for a panel discussion based on the recently published

IFPRI Food Policy Report "Agricultural Research - A Growing Global

Divide." The report may be downloaded at

www.ifpri.org/pubs/fpr/pr17.asp.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nienke Beintema -- Head of the Agricultural Science and Technology

Indicators (ASTI) initiative, International Service for National

Agricultural Research Division, International Food Policy Research

Institute

Philip G. Pardey - Professor, Department of Applied Economics and

Director, International Science and Technology Practice and Policy

(InSTePP) Center, University of Minnesota, St. Paul

Dana G. Dalrymple -- Senior Research Advisor, Bureau of Economic

Growth,

Agriculture and Trade, U.S. Agency for International Development

Isi A. Siddiqui -- Vice President for Science and Regulatory Affairs,

CropLife America

IFPRI is pleased to invite you to the following Panel Discussion, which

we will hold in our fourth floor conference facility located at 2033 K

Street, NW (entrance on 21st Street, between K and L Streets). Please

RSVP to Simone Hill Lee (s.hill-lee@cgiar.org; Tel: 202.862.8107).

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

EVENT: Agricultural Research -- A Growing Global Divide

Labels:

Events

Friday, October 27, 2006

IFPRI EVENT: Distributional Effects of WTO Agricultural Reforms in Rich and Poor

Thomas W. Hertel, Purdue University

Thursday, 2 November, 2006. 3:30 - 5:00 p.m.

The presentation is based on a paper by Thomas W. Hertel and Roman

Keeney of Purdue University, and Maros Ivanic and L. Alan Winters, The

World Bank, for the 44th Panel Meeting of Economic Policy in Helsinki,

Finland, October 2006.

Paper Abstract

Rich countries' agricultural trade policies are the battleground on

which the future of the World Trade Organization's troubled Doha Round

will be determined. Subject to widespread criticism, they nonetheless

appear to be almost immune to serious reform, largely because of the

widespread belief that they protect poor farmers. Our findings counter

this view. Using detailed data on farm incomes, they show that only

large, wealthy farmers in a few heavily protected subsectors would be

seriously affected by trade reform. By contrast, reforming rich

countries' agricultural trade policies would lift large numbers of

developing country farm households out of poverty, according to an

analysis using household data from 15 developing countries. In most

cases, these gains are not outweighed by the poverty-increasing effects

of higher food prices among other households. The analysis conducted

here indicates that maximal trade-led poverty reductions occur when

developing countries participate more fully in agricultural trade

liberalization.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thomas W. Hertel is a Distinguished Professor at Purdue University,

where he teaches and conducts research on the economy-wide impacts of

trade policies. He is the founder and Executive Director of the Global

Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) which encompasses 5,000 researchers in

over 100 countries around the world.

IFPRI is pleased to invite you to the following Policy Seminar, which

will be held in our fourth floor conference facility located at 2033 K

Street, NW (entrance on 21st Street, between K and L Streets). Please

RSVP to Simone Hill Lee (s.hill-lee@cgiar.org; Tel: 202.862.8107).

Thursday, 2 November, 2006. 3:30 - 5:00 p.m.

The presentation is based on a paper by Thomas W. Hertel and Roman

Keeney of Purdue University, and Maros Ivanic and L. Alan Winters, The

World Bank, for the 44th Panel Meeting of Economic Policy in Helsinki,

Finland, October 2006.

Paper Abstract

Rich countries' agricultural trade policies are the battleground on

which the future of the World Trade Organization's troubled Doha Round

will be determined. Subject to widespread criticism, they nonetheless

appear to be almost immune to serious reform, largely because of the

widespread belief that they protect poor farmers. Our findings counter

this view. Using detailed data on farm incomes, they show that only

large, wealthy farmers in a few heavily protected subsectors would be

seriously affected by trade reform. By contrast, reforming rich

countries' agricultural trade policies would lift large numbers of

developing country farm households out of poverty, according to an

analysis using household data from 15 developing countries. In most

cases, these gains are not outweighed by the poverty-increasing effects

of higher food prices among other households. The analysis conducted

here indicates that maximal trade-led poverty reductions occur when

developing countries participate more fully in agricultural trade

liberalization.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thomas W. Hertel is a Distinguished Professor at Purdue University,

where he teaches and conducts research on the economy-wide impacts of

trade policies. He is the founder and Executive Director of the Global

Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) which encompasses 5,000 researchers in

over 100 countries around the world.

IFPRI is pleased to invite you to the following Policy Seminar, which

will be held in our fourth floor conference facility located at 2033 K

Street, NW (entrance on 21st Street, between K and L Streets). Please

RSVP to Simone Hill Lee (s.hill-lee@cgiar.org; Tel: 202.862.8107).

Labels:

Events

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

International World Food Day. Oct 16

Hello,

Last week we celebrated the International World Food Day (WFD), as well as, the creation of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization in 1945. Coincidence or not, FAO has been working extensible in the reduction of food insecurity around the world, and Nicaragua is not the exception.

There is now a global consensus on the fact that the fight against hunger requires a comprehensive approach: is not just about increasing yields as it used to be. The fight against hunger is also about creating new markets, promoting conservation and valued added practices, organizing the communities, and, of course, ensuring jobs and education. To accomplish these, however, there must be an alliance among the different components of a society e.g. government, NGO’s, donors, private sector. Our program on School Gardens is a good example of how different sectors can get together and work towards a common goal, food security. Bellow find a video FAO-PESA prepare for the WFD 2006.

Enjoy.

Last week we celebrated the International World Food Day (WFD), as well as, the creation of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization in 1945. Coincidence or not, FAO has been working extensible in the reduction of food insecurity around the world, and Nicaragua is not the exception.

There is now a global consensus on the fact that the fight against hunger requires a comprehensive approach: is not just about increasing yields as it used to be. The fight against hunger is also about creating new markets, promoting conservation and valued added practices, organizing the communities, and, of course, ensuring jobs and education. To accomplish these, however, there must be an alliance among the different components of a society e.g. government, NGO’s, donors, private sector. Our program on School Gardens is a good example of how different sectors can get together and work towards a common goal, food security. Bellow find a video FAO-PESA prepare for the WFD 2006.

Enjoy.

Labels:

Food Security,

Nicaragua,

School Gardens,

Video

Saturday, October 21, 2006

Un poco de Quejas

Saludos

Voy a escrivir en espanol pues la verdad es que me tengo que quejar un poco, y esto lo hago mejor en espanol. Las eleciones en Nicaragua estan a la vuelta de la esquina y todo parece indicar que Daniel Ortega podria ganar inclusive en la primera vuelta, con un poco mas del 30% de los votos. Esto, gracias a una estupida ley concorda entre mienbros del PLC (Partido Liberal Consituyente) y el FSNL (Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional). Las perspectivas de que los Danielistas retomen el poder nublan y cubren de incertidumbres un futuro nicaraguense que empiesa a salir de la sosobra. Solo para dar un ejemplo del nivel de atrazo que llevo la revolucion al pais, en este ano se alcanzaron los niveles de exportacion del 1976.

Pueda que el nivel de exportaciones no sea el mejor indicador para medir la properidad de un pais, sobretodo en el caso de Nicaragua pues este sector ha sido controlado ferozmente por un pequeno grupo de agroempresarios. De todas formas, no hay quien pueda negar que el fortalecimiento del sector agricola tiene efectos directos e indirectos en la reducion de probeza y la prosperidad social. Entonces el que los Sandinistas con sus politicas subsidiadoras e irracionales que llevaron al sector agricola a niveles de los anos 40 tengan la posibilidad de retomar es una razon logica para quejarme.

La otra razon para quejarme es que se me dano mi computador. Aparentemente, la Dell portatiles tiene problemas con los Disipadores de Calor (heat sink). El computador se calento tanto que afecto la targeta procesadora. Es tan grande el problema, que parece que toda mi informacion recopilada en ese computador por mas de 3 anos esta seriamente amenazada.

Seguire a la espera de un milagrito, no sin antes disculparme por la falta de egnes y los errores autograficos.

Voy a escrivir en espanol pues la verdad es que me tengo que quejar un poco, y esto lo hago mejor en espanol. Las eleciones en Nicaragua estan a la vuelta de la esquina y todo parece indicar que Daniel Ortega podria ganar inclusive en la primera vuelta, con un poco mas del 30% de los votos. Esto, gracias a una estupida ley concorda entre mienbros del PLC (Partido Liberal Consituyente) y el FSNL (Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional). Las perspectivas de que los Danielistas retomen el poder nublan y cubren de incertidumbres un futuro nicaraguense que empiesa a salir de la sosobra. Solo para dar un ejemplo del nivel de atrazo que llevo la revolucion al pais, en este ano se alcanzaron los niveles de exportacion del 1976.

Pueda que el nivel de exportaciones no sea el mejor indicador para medir la properidad de un pais, sobretodo en el caso de Nicaragua pues este sector ha sido controlado ferozmente por un pequeno grupo de agroempresarios. De todas formas, no hay quien pueda negar que el fortalecimiento del sector agricola tiene efectos directos e indirectos en la reducion de probeza y la prosperidad social. Entonces el que los Sandinistas con sus politicas subsidiadoras e irracionales que llevaron al sector agricola a niveles de los anos 40 tengan la posibilidad de retomar es una razon logica para quejarme.

La otra razon para quejarme es que se me dano mi computador. Aparentemente, la Dell portatiles tiene problemas con los Disipadores de Calor (heat sink). El computador se calento tanto que afecto la targeta procesadora. Es tan grande el problema, que parece que toda mi informacion recopilada en ese computador por mas de 3 anos esta seriamente amenazada.

Seguire a la espera de un milagrito, no sin antes disculparme por la falta de egnes y los errores autograficos.

Labels:

En Español,

Nicaragua,

Politics

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

Elections in Nicaragua: Two Contrasting Paths to Choose

Hola Gente,

We're less than a month away from the presidential elections of Nicaragua, yet it seem that the voting is taking place tomorrow: the whole country is flooded with unregulated expensive political advertising (see the picture), the parties' caravans are seem everywhere making traffic worse, and politics is in everybody's conversations regardless of where you are. Since my arrival to Nicaragua, people tell me that these are the most decisive elections in recent history. And they are definitely right.

So without forgetting our topic agriculture, let’s talk about politics for a bit as they have a direct effect on the welfare of the rural sector and the fate of agriculture (check out this post). Since the end of the Sandinista Revolution in 1989, Nicaragua has seen bipolar election campaigns: you voted for the Sandinistas or against the Sandinistas. The Sandinistas, always represented by Daniel Ortega in the FSLN party lost to; Violeta Chamorro (1990), to Arnoldo Aleman (1997) and to Enrique Bolanos (2002). Until then, the run for president was solved easily because the Sandinistas haven't been able (since 1990's) to get more than 35% of the popular vote.

This changed drastically when Aleman signed "el Pacto" (a political pact) with the Sandinistas in which some key political figures of the FSLN got permanent government positions and other political favors. This pact improved the condition of the FSLN and in return Aleman received lax treatment when his corruption charges surfaced the public. The spillover effect, however, was a strong division in the two parties which saw the pact as ideologically incongruous and driven by personal ambitions of Aleman and Ortega. The results were the following: liberals against the pact (ALN) and for the pact (PLC), and Sandinitas against the pact (MRS) and for the pact (FSLN).

Now according to polls, the Daniel Ortega (FSLN) leads with 30% of the vote, followed by Eduardo Montealegre (ALN) with 25%, Mundo Jarquin (MRS) with 15%, and Jose Rizo (PLC) 10%. Because this distribution has never taken place in the recent history of Nicaraguan, there is an overwhelming sense of uncertainty that maintains the country on a frustrating status quo. Besides the unique campaign distribution, there has also never been a runoff election in Nicaragua before, and the amount of people expected to vote appears to be unprecedented, raising questions about logistics and transparency.

What is best for the country? You may ask. This is, of course, up to the Nicaraguans to decide. That is not to say, however, that the outcome of this election will have a direct effect in Central America and possibly in the whole continent. In my opinion, Nicaraguans have to choose between a prosperity path that guarantees economic, political, and social freedom, and an already traveled path of isolation, injustices, and poverty. Although these may sound like plain broad words, I believe the voting decision of the Nicaraguans boils-down to these two paths.

The former path is represented by both Montealgre and Jarquin. Montealegre, who I had the opportunity to speak with, will ensure economic prosperity with a broad growth agenda. Jarquin, also an economist, promises sustain growth and social equity. In my opinion, Nicaraguans must be practical a vote for Montealegre as he is the one with the highest chances of winning. This election is too important to take the risk of voting for a candidate with a slight chance of winning, and only Montealegre ensures a strong vote.

Looking at my notes on Montealgre's presentation at George Washington University in Washington DC (06/15/2006), I find a candidate prepare to run the country in the right direction. Putting emphasis on transparency, economic growth, government institutions, education, and health, he has the silent support of most governments in the region (U.S support for him is controversially quite noisy). When asked about agriculture, he talked about the importance of both creating new markets for export commodities, and assisting small farmers with technical, commercial, and financial help. With an almost nonexistent local market for agricultural output in Nicaragua and with the new set of trade agreements, focusing in exports is a wise policy.

From the time when Violeta Chamorro defeated the face of the revolution in the 1990’s presidential election, Nicaragua has traveled a bumpy road similar to the thousands that lead to the rural areas. Yet, the momentum gain until now is priceless as it has built the foundations for strong growth and stability. I hope this stability is not shaken by the usual earthquakes, not geological but political, that affect the country so often. Daniel Ortega remains an enormous threat to the future and prosperity of the country and must be defeated once for all.

I finish the post providing a link to an interesting article published by the Washintopost.com. The author Roger F. Noriega from the American Enterprise Institute (conservative think tank) talks about the possible scenarios for Nicaragua in this election. Click HERE the read the article.

Monday, October 02, 2006

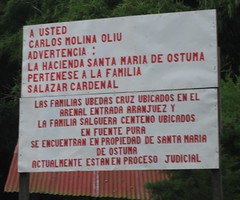

Nicaraguan Agriculture: Private Property and the Revolution's Legacy

Private property in Nicaragua is a dubious concept in the process of being rediscovered. The country is been recovering from the revolutionaries years in which most of the productive land was confiscated by the Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional (FSNL) and reorganized into cooperatives and Unidades de Produccion Estatal (UPE. State Production Units). The policies enacted during the revolutionary period created repercussions still seen today: farms with several titles, families disunited, violence over land ownership, and most important, a huge lost in agricultural productivity and national welfare.

The initial plans of the revolution of 1979 were to take possession of all the property own by Somozas’ family or by someone else who had gained it through positions within the dictatorship. There was little opposition to these actions as the Somoza regime had control and ownership of whole range of companies in several sectors: mining, construction, agriculture, banking etc. Before the revolution, even the well-off private sector was getting uncomfortable with the dynasty because they saw it as unfair state competition. For the general NIcaraguan public, this was just one of the many reasons to hate the regime and hope for change.

The initial plans for change, however, would resemble little to what most Nicaraguans had hopped the so-called “land reform” would bring. In fact, after Somoza and its followers were striped away of all property, the Sandinistas created another law in which anyone absent from Nicaragua for more than 6 months would have their property taken away.

These laws created an atmosphere in which private property was constantly been violated and confiscation became a normal routine. The allocation of lands and properties was completely based in clientelism bias towards sandinitas and, of course, those within the party would get the largest chunks. Holding a position in a public office was a tool to return favors to those you like, a patronage system still very common today and very similar to the years of the dictatorship. Talk to Nicaraguans and you’ll hear hundreds of stories of poor families that had their couple acres taken away by the Sandinistas, not because they were relatives of Somoza or because they went outside Nicaragua, but just because their land was nice to the eyes of somebody with party connections.

It didn’t matter anymore if you had been a staunchly opponent of the Somoza regime and had even supported the revolutionary effort, if you own a farm with cattle, cotton, tobacco, coffee, sugar cane or other goods, chances were that it would be confiscated under the most irrational excuses.

Not surprisingly, the productive sector of Nicaragua went into exile, jointed or financed the counter revolutionary force, or simply gave up. These actions affected the country’s economy enormously: in Esteli, the town where I live, after the Sandinistas took power, the owners of the tabacaleras (tobacco processing plants) ran away fearing retributions from the FSNL. Without owners and technicians, the plants were abandoned and thousands of women went unemployed.

Same story with sugar cane mills, coffee farms, and cotton plantations. Of course the U.S trade embargo played an important role in the economic crisis as the U.S was one of the main clients of Nicaraguan goods. However, the effect of the embargo was shorttermed and miniscule against the disincentives created by the Sandinistas in the agricultural sector as a whole.

Disincentives and lack of rationale was common place in the agricultural sector during those days. For instance, the Sandinistas tried to promote the utilization of Central Pivot Irrigation systems, a result of the latest in technology in the developed world. Of course, for a former farm worker who could barely read and write this new piece of technology resulted simply unsuitable. The irrigation pipes probably end up melted, same fate suffered by the Robotic Milking Systems, imported from Eastern Europe.

But this nonsense top-down, technology transfer approach to agriculture was not the only reason for failure: the social structure of the rural sector was also disrupted. Farmers where not allowed to commerce their goods, even in miniscule amounts. All output needed to be collected, transported, store, and sold by the government. Ignoring the common traditions of the rural people and imposing an alien Marxist system on them was deemed to fail.

Another ridiculous policy took place when it came to harvesting the crops: thousands of students from the cities were sent to the rural regions to do these tasks. Without any experience, away from their families, and under very harsh conditions, it resulted impossible to expect a high school kid to collect cotton or to cut sugar cane under the inferno heat of Chinandega. Some farmers would even reject the students knowing that they could easily ruin the plants and the harvest. Thankfully, the policy was dropped after three years.

Finally, another disincentive created by the Sandinistas was the so called “Piñata” in which farmers were given almost everything for free. Free land, free seeds, free technical assistance, and even free labor, all resulting in a rural sector that still wants everything for free. Visit the farmers today and see their faces when you tell them of their financial contribution to the project, not happy certainly. This dependacy in foreign assistance (central government, or aid agencies), I think is, a rooted problem that will take generations to solve.

Nicaraguan agricultural sector during the Sandinista years served as a sort of playground for the politicians in the central government who tried to implement what translated Marxist literature said. This improvised lab resulted on a series of failures still seem today. With almost 30% of the population undernourished, is depressing to realize that this was a direct result of a bunch of revolutionaries trying to “help” the people.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)