Hello,

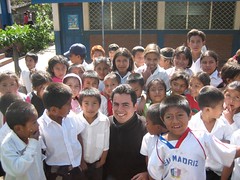

The picture was taken in a school at San Jose de Cusmapa, Madriz. This state one of has the worst food insecurity indicators in Nicaragua.

Bellow is a summary of the School Garden project we're conducting. The report is not ready yet so this is rather a draft, yet it has some info you may find useful.

Project Rationale and Priorities

The main objective of PESA Nicaragua is to contribute to the access and availability of food and to improve the nutritional situation of the 16 municipalities where the project currently exists.

One of the many initiatives to achieve such objective is through the implementation of school gardens which are improving the food security of the communities where they are being grown. This is done mainly through both education and production. The gardens are used as tools for the teaching of the concept of nutrition, e.g. the importance of a balanced and diverse diet. The garden activities engage children more than the traditional confines of the classroom, guaranteeing a clear understanding of food and its role in their wellbeing.

A school garden encourages local children to transfer the gardening techniques learned in the school garden to gardens in their homes, introducing new vegetables into their diets and that of their families. In addition, the garden products can be used as complements to a School Lunch Program, whereby food can be taken home by the kids, or sold at the local markets.

Although school gardens around the world have been used to generate income, promote community participation, and improve the teaching of applied curriculum activities, the priorities of this project are the effective teaching of a) nutrition and b) practices of growing vegetables and other foods. This is not to say that the other components mentioned above are not important. In fact, there are some schools where the teaching of science, math, and other assignments through community gardens is achieved with good results. Nevertheless, FAO through the PESA project expects augmented nutritional and production patterns in the communities where the project is been implemented.

Such impact should be measured through: improved understanding of nutrition; recognition and consumption of new vegetables and fruits; creation of home gardens at the children’s homes; and, of course, a reduction of under-nutrition indicators.

Location and Size

The representation of FAO in Nicaragua has been working in school gardens for the past year. Thus far, FAO-PESA in alliance with members of the private, civil, and public sectors (see annexes) have set up about 60 gardens in the north and central region of the country, prioritizing those counties with severe under-nutrition indicators. The school gardens are mainly found in rural communities, but there are some gardens that have been implemented in the peri-urban belt of Managua.

There are about 14,000 students participating in the gardens in six different Nicaraguan states. In addition, 450 teachers, extension agents, and social workers have been trained to set up and oversee the school gardens.

Beneficiaries

The FAO-PESA provides training in setting up and running a school garden to extension agents of private and public entities, social workers, teachers, instructors, and parents. Nonetheless, the main beneficiaries of the school garden project are the children and their families. The project also expects positive influence on the community as a whole, resulting from better community organization, improved school environment, and, of course, healthier and brighter children.

Main Components

The methodology of the project can be divided into four main components: 1) Organization; 2) Education; 3) Nutrition; and 4) Production.

PESA considers community organization as one of the main means of achieving its goal of improved food security. Organization is key for guaranteeing the sustainability of the school garden project and the involvement and commitment of the participant agents. Before implementing the garden, the project assesses the level of interest of the parents, teachers, students, and other participant organizations in the area. If the level of organization and enthusiasm is adequate, committees are formed with specific tasks, e.g. watering, harvesting, security, etc. The parents participate in the committees conducting heavy labor that is inappropriate for children. They also play a crucial role during vacations as they have to ensure that the gardens are well maintained.

Education is another important component of the project as gardens can be used as tools in practical curriculum. Advocates of experimental learning like Jean Piaget and Maria Montessori have acknowledged the tremendous success of these techniques. School gardens can be used in subjects such as math, science, environmental studies, and even writing and arts. At a recent meeting, teachers were eager to show us the result of creative artistic work for labelling the garden beds and other decorations inside the garden. Also, the change of environment from a classroom to the garden has proven to provide positive impacts in the learning capabilities of children. California is a leading example in this area, as the state-wide campaign for greening the schools and using gardens for applied curriculum have had excellent results.

Nonetheless, the primary curricular component that the project wants children to clearly understand is nutrition. The project believes that a positive difference in food security can be made by changing the diet patterns of children at the school and, subsequently, at home. As a result, school gardens are used to introduce new vegetables that already exist in the communities but are not widely consumed. In addition, healthy snacks such as fruit and some vegetables are being encouraged as replacements for packaged munchies and sodas. Changing the diet habits of an adult is far more difficult that changing that of a child, and if the children are participating in the production of such new products, incorporation into the diets of children will be much easier.

The last subject is no less important than the others. Good production and a healthy garden are essential to keep the participants motivated and enthusiastic. In this regard, the project provides training in vegetable production using different techniques such as drip irrigation, raised bedding, tire gardening, and Earth Boxes (see annexes). Training in weed and pest management is also provided emphasizing the used of local resources and organic pesticides. For instance, neem tree seeds have been used widely as a repellent against Aphids, Coccoids, and Lepidoptera.

As mentioned before, the outcome of the garden is used in the school kitchen as a complement of a school nutrition program. However, there is no way a school garden will be able to replace such a program. Gardening is a difficult task that depends in a lot of variables like water, soil, light, pests, inputs, labor, etc. Thus, having a school food program that relies solely on the products from the garden is unwise and could put children in jeopardy.

There is evidence, however, of some school gardens in Sub-Saharan countries that depend on the school gardens to provide for a feeding program. Similarly, there are school gardens that effectively sell their harvests, process the food into value added, and obtain significant income from the gardening activities. Yet, these tend to be schools with decades of experiences at gardening, and under different conditions of those in Nicaragua.

Cost and Benefits

A cost-benefit analysis has been challenging to put in place as most of the benefits of the garden take the form of intangibles. There is still much controversy in the economic literature regarding the quantification or returns of benefits such as education, improved nutrition, better organization, etc. In this regard, my study lacks the tools and the time to gather primary information for a strong qualitative data set. However, I’m relaying on other studies to estimate the contributions of improved primary education, enhanced nutrition on children, and superior communal organization. Such studies quantify lost revenue for not having a school degree, or the forfeited wages due to illness, an indirect cause of malnutrition.

The only quantifiable benefit in a school garden project is the production coming out of the gardens. In this regard, garden production can be quantifiable by estimating the output per square meter and the commercial price of vegetables such as tomatoes, radishes, cucumbers, squash, onions, and beets among others. The results so far show that the financial contribution of such production is minimal compared to the investment required in setting up a school garden. However, students and parents have expressed in different workshops the advantage of not having to spend money in some items of their food basket. On this point, I have to emphasize that we are working with communities making less than two dollars a day, so small savings coming from the garden production are greatly appreciated.

Concerning the cost calculations of the project, the study has determined that it costs about US$300.00 to set up a garden with the necessary inputs for a year of production. Included in these calculations are tools, worm castings or compost mixture, fertilizer, some organic pesticides, seeds, and transport. I am in the process of calculating cost of technical assistance and opportunity costs of all the participating agents in the garden.

From a rigid financial point of view and assuming production to be the main benefit, gardens are an inefficient tool, as the school will be better off by obtaining the vegetables at the local market. This action would save time for both teachers and students, increase school space, make access to food more reliable (free from worries about pests and other problems), and contribute to the local economy by purchasing from nearby farmers. It may even be the case that the total quantity of food that US$300.00 can buy over a year is higher than what a garden could produce during the same period of time, implying that a cash transfer is a wiser option.

Nevertheless, the main benefits of the school garden are not on the production side. As mentioned before, they can be summarized in a better understanding of nutrition, so the children can make more educated decisions regarding their diets. Changes like the diversification of consumption patterns that include more and new vegetables and fruits that can be accessed locally is the project’s main goal. These changes will guarantee a reduction in malnutrition levels, and the adequate presence of micro nutrients that are so essential for the development of children and their future livelihoods. Therefore, school gardens appear to be an appropriate tool in the fight against food insecurity.

Main Issues

Even though Nicaragua has seen initiatives of school gardens dating back to the 40’s and 50’s, the sustainability of such programs has never been ensured. The U.S., under the Alliance for Progress (former USAID) promoted the use of gardens widely. In a similar way, and under the pressure from food scarcity, the Sandinista government sponsored in the 1980’s a nation-wide strategy for the implementation of school, community, and home gardens. However, the school gardens have never been implemented into the school curriculum, and no national agency has taken responsibility for their sustainability. Most of the promoters came from the civil sector and acted in an Ad Hoc way, with few linkages to research, extension, and educational intuitions of Nicaragua.

Although these aspects have been changing progressively (the Ministry of Education signed an agreement for a pilot program with school gardens and Nicaragua’s Agricultural Research and Extension Institute has been of the main participants of the school garden project), the sustainability of the school gardens in term of funding, technical support, and other aspects remains uncertain.

Another drawback of the school gardens is technical assistance. Vegetable gardening in particular requires careful oversight as these crops tend to be extremely susceptible to water depravation and vulnerable to a host of pests. So far, the amount of literature available to the instructors at the schools is limited. Although there are several manuals and guides in school gardening, the project is in the process of adapting those to the local circumstances.

The project is also using a technology called Earth Boxes. A close facsimile to tire gardening, the boxes maximize water usage and vegetable production (www.earthboxes.com). Although the sustainability of this technology is questionable as each cost about US$40 (they have been donated by Growing Connections), the boxes bring to the garden an attractive component that makes students and instructors more willing to participate.

The last issue has to do with the way many people in the project and at national institutions see school gardens. For them, gardening has no place at a school and sees no connection between a school garden and education and nutrition. These are typical misconceptions that will take time to change.

Annexes

List of organizations participating in the School Garden Project. NGO (1), Government (2), Private Sector (3)

Alcaldía de Managua. 2

Fundación COEN. 1

Fundación Familia Fabreto. 1

INPRHU. 1

Alcaldía de Las Sabanas. 2

CISA Exportadora. 3

INTA. 2

Fe y Alegría. 1

Europa Motor. 3

Café Soluble. 3

Continental Airlines. 3

Ganadería Santa Elisa.3

Cristiani Sánchez. 3

Química Word. 3

Televicentro Canal 2. 3

BANCENTRO. 3

Kola Chaler. 3

CARLAFISA. 3

Enrique Zamora. 3

COASTAL. 1

Fundación Pantaleón. 1

"it is imposible to fight poverty when we pay the poor to remain that way" something like that, but you get the message right?. Milton Friedman

3 comments:

Rafael, We're starting a home gardening program here in Granada as an extension of the school gardening program begun last year here. I'm new to gardening in Nicaragua and would like to avoid any pitfalls that you've discovered. Is there a part of your report that covers what worked, didn't work, could have worked better. I'd like to incorporate a composting program into our gardening and keep the whole operation as self-sufficient as possible with a miniumum of external inputs. I'd like to hear more about your successes in Nicaragua. saludos, Rob Keddy casasilas@gmail.com

Hello,

I am also working with gardening in Nicaragua, currently on a permaculture farm, but we are hoping to extend our efforts out to the nearby village. Would you be willing to contact me to discuss more specifics of your project? I would really appreciate that.

Thanks!

Cat

catherine.r.magill@gmail.com

Hi Rafael,

I am Peace Corps Volunteer in Granada, Nicaragua and I am trying to start a school garden at my school. I have never started a garden before and I'm just so overwhelmed with everything I need to do before actually working on the garden. I'm in the process of writing a letter of solicitude with the directora at my school and we're not sure if INTA, Vision Mundial, and MARENA are going to be able to provide us with the resources we need. Can you help? If you could give me some information about resources and about organizations I can go to for help, that would be great. My email is: dianne.y.kim@gmail.com.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Dianne

Post a Comment